His Own Worst Critic

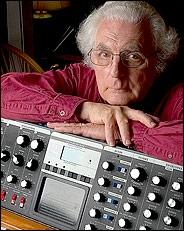

Sonny Rollins's best album in nearly three decades is the healing force of the universe

by Francis Davis

August 29th, 2005 5:31 PM

Without a Song: The 9/11 Concert

Milestone

John Updike still hasn't solicited my advice (start work on Rabbit Has Arisen pronto), but during a phoner in 1992 Sonny Rollins asked if I could recommend a good young drummer. I immediately suggested Reggie Nicholson—whom Rollins said he'd coincidentally just hired, strictly on a trial basis, on somebody else's recommendation. Nicholson "supplied color and audible snap even on ballads and followed Sonny unerringly through a dozen or so choruses of 'Long Ago and Far Away,' " I reported in the Voice, following Nicholson's debut with Rollins in Philadelphia. "It looks like Rollins has finally found himself a drummer." I should have paid closer attention to Rollins's mood backstage after the gig. "Wow, the set really turned a corner during your fours with the drums on the Jerome Kern song," I gushed. "Well, something happened then," he replied—and like a fool, I assumed he was agreeing with me. Maybe my rooting interest clouded my judgment, or maybe all Rollins wanted by that point was a compliant timekeeper, not someone who returned his jabs like Max Roach in the '50s. Nicholson finished the tour, then never heard from Rollins again.

It's become a commonplace of jazz criticism to note that Rollins's studio recordings since the 1970s have barely hinted at the rapture he can induce in concert on any given night. Yet I can't count the number of times I've seen him bring an audience to its feet only to sense great displeasure in his performance from his own body language—these are nights a seasoned Rollins watcher knows there won't be an encore no matter the sincerity of our demand. Rollins may be his own worst critic in more ways than one, which is why many of us didn't dare hope for too much when it was announced earlier this year that he was auditioning concert tapes he'd recorded himself, along with those sent to him by a private collector, and had chosen a 2001 Boston show as his first live release since 1986's G-Man. Without a Song, recorded less than a week after 9-11, finally shipped yesterday, and—forget G-Man —it's Rollins's mightiest effort since Don't Stop the Carnival almost 25 years ago.

No, it isn't the Sonny Rollins album we've been dreaming of for decades, and I don't need him or anybody else to tell me why. Complaining that trombonist Clifton Anderson and pianist Stephen Scott aren't in Rollins's league hardly seems fair, because who is? Anderson has developed a burly, ingratiating presence, and Scott skips along nimbly in octaves on "Where or When" and the title track, even if I could do without his Jarrett-like singing along. The problem is the string-of-solos format: When Rollins goes first, everything else is anticlimactic, and when he goes last, as is more often the case, the wait seems forever—you wish he'd give trombone and piano their own features and grab the spotlight. Why have Bob Cranshaw play electric bass if all you ask him to do is walk? The constant buzz is a distraction, and an upright would blend more handsomely with the wood in Rollins's cello-like lower register.

Adding Kimati Dinizulu's hand percussion to Perry Wilson's traps doesn't intensify the groove: With both of them going at it, the rhythm section just sounds busy. And Rollins's opening head arrangements of four standards, including "Why Was I Born?" and "A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square" (routines, bands used to call them), are superfluous time killers. Better he should just come out blowing—we'd recognize the tunes from his spontaneous embellishments.

Why am I so wild about Without a Song, then? First, no recording since his RCAs in the '60s has more faithfully captured Rollins's sound—on "Global Warming," the program's requisite calypso, his tenor saxophone is a steel drum and its spreading low notes shake your insides. Then, too, even though our national unity after 9-11 now seems a quaint memory, along with that sense of being more sinned against than sinning, maybe I'm responding to the emotionalism of the occasion, just as Rollins and the Boston audience did. In Downbeat a few months after the attacks, a fellow critic I won't embarrass by naming speculated, "while it's still too early too tell what the long-term effect on cultural expression will be . . . there's hope that substance will win out over fluff, that relevance will count for more than entertainment for its own sake, that emotion will triumph over self-serving technique, that art will trump commercialism." Trust Downbeat to wonder if a national tragedy will be good for jazz. Rollins, who lives in Woodstock but was in his penthouse pied- six blocks away from the towers when the planes hit, and who had to be guided downstairs by rescue workers the following day, after the building lost power, wasn't making any promises. "Maybe music can help," he says at one point. "I don't know. But we have to try something."

Rollins's quotes from other songs can be a tip-off to his frame of mind, and the ones that jump out here—"This Is My Lucky Day," "The Farmer in the Dell," and "Oh! Susanna" not once but twice—are ebullient. The last five minutes of "Global Warming"—all Sonny, with Anderson and the rhythm section vamping—are pure bliss, and so are Rollins's games of catch-up on "Why Was I Born?" and "Without a Song," whose melodies he stutters into abstraction, holding the beat in abeyance, before resolving the tension with legato outpourings on the turnarounds. Virtuosity on this level is always thrilling, but when the need arises, it can also be a balm.

Without a Song is reportedly the last album Rollins owes Milestone, his label since 1972, under the terms of his current contract. Concord Jazz now owns Fantasy, Milestone's parent label, and if Rollins no longer feels any loyalty and decides to leave, Blue Note and Verve figure to be right there waiting. A major would spring novel ideas on him, and this wouldn't necessarily be a bad thing. A tussle with Ornette Coleman, Lee Konitz, or David S. Ware and Matthew Shipp? An album of Billie Holiday songs with Bill Charlap? A Stephen Foster project? Taping all of his concerts and choosing the best material for release, forgoing the studio altogether? I've got plenty of ideas. Including this hot young drummer I know.